Taleb’s classical metaphor: “A turkey is fed for a 1000 days—every days confirms to its statistical department that the human race cares about its welfare ‘with increased statistical significance’. On the 1001st day, the turkey has a surprise.”

Some quotable quotes from Taleb’s essay:

“Statistical and applied probabilistic knowledge is the core of knowledge; statistics is what tells you if something is true, false, or merely anecdotal; it is the “logic of science”; it is the instrument of risk-taking; it is the applied tools of epistemology; you can’t be a modern intellectual and not think probabilistically—but… let’s not be suckers. The problem is much more complicated than it seems to the casual, mechanistic user who picked it up in graduate school. Statistics can fool you. In fact it is fooling your government right now.

“By the “narrative fallacy” the turkey economics department will always manage to state, before thanksgivings that “we are in a new era of safety”, and back-it up with thorough and “rigorous” analysis. And Professor Bernanke indeed found plenty of economic explanations—what I call the narrative fallacy—with graphs, jargon, curves, the kind of facade-of-knowledge that you find in economics textbooks. This is the find of glib, snake-oil facade of knowledge—even more dangerous because of the mathematics. (…) I have nothing against economists: you should let them entertain each others with their theories and elegant mathematics, and help keep college students inside buildings. But beware: they can be plain wrong, yet frame things in a way to make you feel stupid arguing with them.

What Is Wise To Do (Or Not Do) In The Fourth Quadrant

(NB: The 4th quadrant basically refers to heavy-tailed or unknown probability distributions with complex or nonlinear payoffs)

1) Avoid Optimization, Learn to Love Redundancy. Psychologists tell us that getting rich does not bring happiness—if you spend it. But if you hide it under the mattress, you are less vulnerable to a black swan. (…) Biological systems—those that survived millions of years—include huge redundancies. (…) Historically populations tended to produced around 4-12 children to get to the historical average of ~2 survivors to adulthood.

2) Avoid prediction of remote payoffs—though not necessarily ordinary ones. Payoffs from remote parts of the distribution are more difficult to predict than closer parts. A general principle is that, while in the first three quadrants you can use the best model you can find, this is dangerous in the fourth quadrant: no model should be better than just any model.

3) Beware the “atypicality” of remote events. There is a sucker’s method called “scenario analysis” and “stress testing”—usually based on the past (or some “make sense” theory).

4) Time. It takes much, much longer for a times series in the Fourth Quadrant to reveal its property. At the worst, we don’t know how long. Things that have worked for a long time are preferable—they are more likely to have reached their ergodic states.

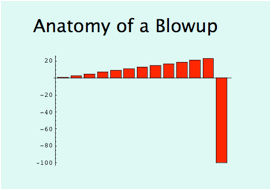

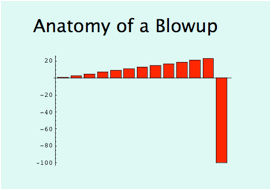

5) Beware Moral Hazard. Is optimal to make series of bonuses betting on hidden risks in the Fourth Quadrant, then blow up and write a thank you letter.

6) Metrics. Conventional metrics based on type 1 randomness don’t work. Words like “standard deviation” are not stable and does not measure anything in the Fourth Quadrant. 70-90% of the Kurtosis in Oil, SP500, Silver, UK interest rates, Nikkei, US deposit rates, sugar, and the dollar/yet currency rate come from 1 day in the past 40 years.