Mi opinión sobre el paquete económico (ingresos y presupuesto) para 2010 aparece en El Universal de hoy (quizá añada un poco más de información más tarde).

Los costos de la hacienda

La discusión y aprobación tanto de los ingresos como del presupuesto de egresos del gobierno federal tiene una naturaleza eminentemente distributiva: produce ganadores y perdedores. A diferencia de otros asuntos que se posponen indefinidamente en el congreso, el debate anual en torno al presupuesto permite analizar como pocos la negociación entre el presidente y los legisladores. Más allá de la retórica donde todos dicen preocuparse por el bien del país, las decisiones hacendarias nos revelan las preferencias de nuestra clase política o los intereses que representa.

En México, los ingresos tributarios han sido históricamente bajos (alrededor de 10% del PIB), comparados con los promedios regionales y de países con ingresos per cápita similares. La baja recaudación –y su dependencia de una renta petrolera volátil y no renovable– restringe la capacidad del estado, además de reflejar un equilibrio político perverso. Por décadas, la renta petrolera ha permitido posponer una reforma fiscal “integral”. Y si el gobierno puede gastar sin exigir impuestos, los ciudadanos se acostumbran a recibir bienes y servicios públicos sin contribuir o sin reclamar demasiadas cuentas por ellos.

En otras latitudes, las izquierdas demandan mayores impuestos y gasto público, mientras que los partidos de derecha exigen una menor intervención del estado en la economía. Pero en México vivimos en un mundo al revés: el gobierno federal, supuestamente de derecha, propone mayores impuestos para preservar el gasto social mientras que la oposición rebate que es una mala idea aumentar impuestos durante una recesión. Pero los matices ideológicos en el debate hacendario resultan inútiles cuando la evasión fiscal y el dispendio públicos son la norma.

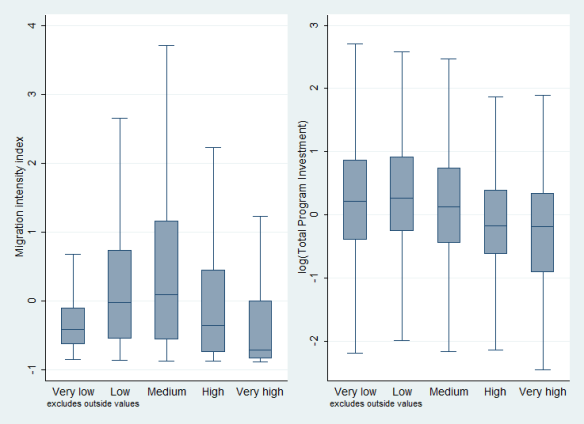

Para tener claro quién gana y quién pierde con el statu quo hace falta una discusión seria sobre la incidencia de los impuestos y el gasto público en México. Por un lado, se equivocan quienes se oponen a establecer un IVA generalizado aduciendo proteger a los más pobres: alrededor de la mitad del subsidio implícito en la exención del IVA a alimentos y medicinas favorece al 20% más rico de la población. Por otro lado, si bien el gasto social ha aumentado en los últimos 15 años, se equivocan también quienes afirman que este gasto, en su forma actual, contribuye a reducir la desigualdad: programas como Oportunidades son bastante progresivos, pero el grueso del gasto redistributivo (educación, salud, pensiones, subsidios agrícolas) es regresivo en términos absolutos, es decir, tiende a beneficiar a los menos pobres. Y ni hablar de la calidad del gasto.

De acuerdo con el Presupuesto de Egresos aprobado esta semana, el gobierno federal espera erogar este año 3.18 billones de pesos–casi 30 mil pesos por habitante. Y se ha dicho hasta el cansancio que cualquier ajuste brusco al presupuesto pondría en riesgo importantes y exitosos programas sociales como Oportunidades. Pero, ¿de qué tamaño es el compromiso con el combate a la pobreza? La propuesta inicial del Presupuesto de Egresos de la Federación contemplaba alrededor de 84.2 mmdp para SEDESOL, de los cuales 38.8 mmdp irían a Oportunidades, es decir, sólo 1.2% de los ingresos totales para 2010. ¿A dónde se va el resto?

El gasto en inversión física se estima en 536.7 mmdp y las transferencias a entidades en 920 mmdp. En contraste, los servicios personales del gasto programable ascenderían a 829 mmdp (26% de los ingresos). Sea cual fuere la rentabilidad social del gasto en burocracia, difícilmente puede considerarse un gasto progresivo.

El crecimiento económico es el mejor remedio contra la pobreza, pero la necesaria provisión de bienes públicos y redistribución del ingreso corresponden al estado. Sin embargo, por muy diversas razones las democracias tienden a favorecer políticas públicas económicamente ineficientes en aras de sostener coaliciones políticas de distinta índole. Nuestro sistema político es aún más proclive a proteger a grupos empresariales del pago de impuestos, y a beneficiar con el gasto a grandes burocracias antes que a la mayoría de los ciudadanos. En gran medida, la ineficiencia e injusticia de nuestra hacienda pública es legado del corporativismo del régimen priísta, pero 12 años de gobiernos sin mayoría en el congreso, y 9 del PAN, hacen corresponsables ya al resto de nuestros representantes. Y si no entendemos por qué las reglas del juego favorecen esto, podemos esperar sentados a que la democracia produzca resultados distintos.